Collegiate teams don’t contend for national titles without talented runners and solid training.

But coach Diljeet Taylor will tell you that winning with a positive culture involves far more.

Last month, Taylor led the Brigham Young University women to second place at the NCAA Cross-Country Championships, the first time they reached the podium since 2003. The University of Arkansas won the title by only six points over BYU.

The Cougars were 23rd at NCAAs the year before Taylor arrived. Her first year they were 10th, then 11th, then seventh. And now, second. Along the way, she’s inspired fierce dedication from her athletes.

“I would say my relationship with her is one of the best relationships I have in my life,” senior Courtney Wayment, 21, who ran 20:16.1 to place fifth in the 6K race, told Runner’s World. Her Instagram bio proclaims her “Taylor Made,” a slogan the women also wore on beanies after the meet.

“She got seven women on the line in their mind saying we can be national champions,” Wayment said. “That’s a pretty remarkable thing for a coach to do. And now, we feel like we can accomplish anything we put our mind to.”

Taylor, 42, said she’s proud of how her women ran but doesn’t gauge her success on results alone. “My biggest daily check is, did I empower someone today?” she said.

Workouts, nutrition, sleep, weight training—all of it matters. According to Taylor, however, the pinnacle of coaching is helping athletes believe in themselves. Here’s how she’s done it, one handwritten note, broken scale, and BYU-shaped butter pat at at time.

She’s honest, even when it’s tough.

As early as Taylor’s first season, she told the team she’d get them back to the podium this year. Placing second transcended their early expectations. Still, to come so close to a national championship and walk away the runner-up stings, Taylor admitted.

“I’m obviously very proud,” she said. “But I am jealous that Lance Harter [of Arkansas] won a national title.” In the weeks since, she’s shared that mix of sentiments with her team, a level of transparency she believes breeds trust.

Junior Whittni Orton, 22, said she appreciates Taylor’s honesty and bluntness. “She doesn't say things she doesn’t mean,” Orton said.

So when Taylor shared her belief in Orton’s potential, Orton said, she couldn’t help but believe her—and subsequently improved her place from 115th the last time she ran NCAAs, in 2017, to seventh this year. “She sees something in you, and she will push you and get it out of you,” Orton said.

She keeps running fun.

As a runner and then coach at Cal State Stanislaus, where she coached men and women for nine years before coming to BYU, Taylor learned happy runners tend to perform better—and make memories outlasting their career. So, she plans regular parties and date nights. When the team travels to races near the ocean, she schedules beach time post-competition. This year, after cross-country camp in Park City, she took 16 women to Hawaii for preseason.

Before bigger meets, she hosts elaborate dinners at her home—they’re “very extra,” Orton said, complete with details like photo place cards, a gift of BYU apparel, and butter shaped like the school’s letters.

This year, the menu included Cardinal chicken and Razorback red potatoes—references to Stanford and Arkansas mascots—and loaves of bread from a local bakery. All season long, the women had been telling each other to “get that bread,” Taylor said. “I have no idea what that means, but I am assuming it’s to do something really good.”

The attention to detail showed her runners she was listening, Orton said. “She’s basically just like one of us, except that this is her job and she’s older,” said senior Erica Birk-Jarvis, 25.

She gets to know each runner personally.

Taylor has two sons—ages 8 and 10—and said she parents them differently. She treats her athletes the same way. “Some need a ton of assurance, and some need you to be really tough on them and really direct with them,” she said.

She uncovers each runner’s inner workings not only in practice, but also in weekly one-on-one meetings and “Tuesdays with Taylor,” an open team lunch in the hallway outside her office where teammates discuss everything from school to relationships to family issues.

As she gets to know them as humans and athletes, Taylor also customizes her runners’ training and race plans. The approach bore fruit at the NCAAs, where Wayment, Birk-Jarvis, and Orton set out with divergent racing strategies.

Birk-Jarvis started fast, while Wayment called herself the sweeper: “Anyone who went out too hard, who didn’t run their race plan, I was going to sweep them up,” she said. They all found each other at the end, crossed the line in fifth, sixth, and seventh, and earned All-America honors for their efforts.

She puts it in writing.

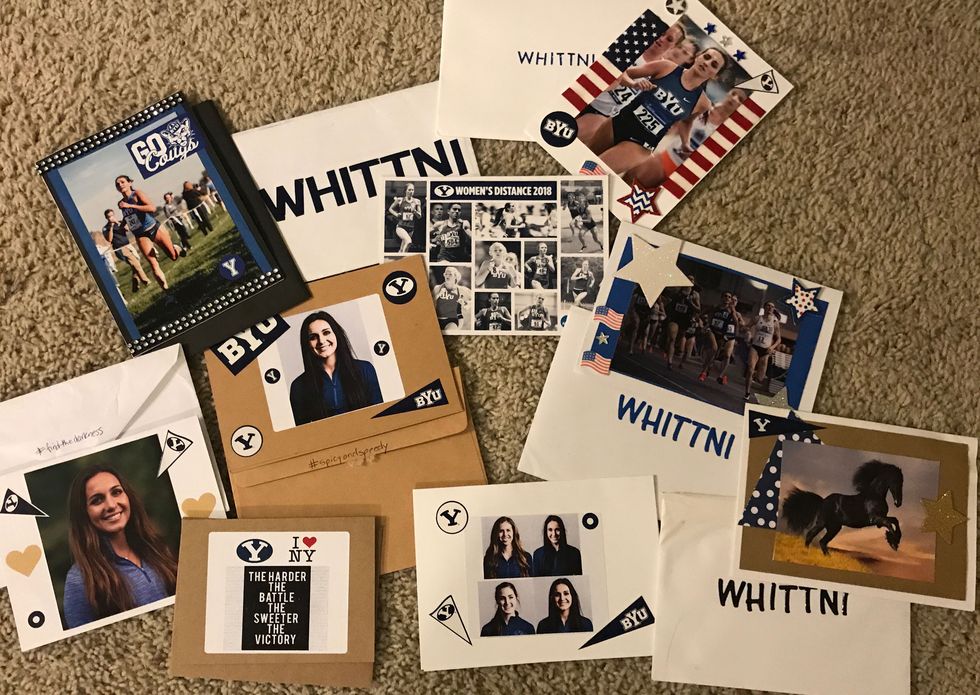

Taylor once received an encouraging note from a high school coach before a section meet. It meant so much to her that for the past decade, she’s hand-written cards to each athlete before every race. As their careers and seasons progress, the notes become more personal and elaborate—bedecked with jewels, stickers, and messages like “You’re a queen,” and “She believed she could, so she did.”

“I have a whole drawer full of them,” Orton said. “It’s nice to go back and read them and see a progression.”

Taylor sometimes stays up until 2 a.m. preparing the missives. During a busy season, it gives her a chance to reflect, and the hand-crafted notes demonstrate her athletes’ value to her and the team. Not that Taylor’s opposed to digital communication. At least twice a week, she sends an inspirational text to everyone, Wayment said—a quote about feminism, maybe, or a bread emoji.

[Build your personalized and adaptive training plan for FREE with Runcoach.]

She sticks with them through ups and downs.

That all Taylor’s talented runners arrived to the start line healthy and race-ready was far from guaranteed. Orton had spent each previous cross-country season injured. Earlier in her collegiate career, Wayment had a stress fracture, then was hospitalized with E. coli. And Birk-Jarvis had a baby, Jack, in December 2017, and almost left BYU and the team entirely.

When Birk-Jarvis learned she was pregnant, she struggled to tell Taylor. “I knew I hadn’t really reached my potential, and I knew we had big plans for the following year,” she said.

Both women cried, and Birk-Jarvis planned not to return to school; Taylor told her to wait to decide. During the year Jack was born—which Birk-Jarvis spent in Canada with her husband, Tyler—Taylor keep the texts coming and communication open.

“I felt like she valued me as a person and a runner and wanted me to come back but also respected my decision if I didn’t feel like that’s what I wanted to pursue,” Birk-Jarvis said. With Taylor’s support, she returned during the summer of 2018—then placed seventh at NCAAs that fall, an improvement from 34th two years earlier.

She gives weight little weight.

Taylor doesn’t do weigh-ins or body fat analysis. She educates herself on issues like disordered eating and RED-S—relative energy deficiency in sport, a mismatch between energy intake and expenditure that contributes to bone injuries and a host of other health problems—with books, online courses, and podcasts.

She also helps inform others. On December 17, she’s giving a talk called “Thin To Win? The Myth Of What It Takes To Be A Successful Distance Runner” at the U.S. Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association Convention in Orlando.

Of course, body composition plays a role in the sport, she said. College students with newfound access to unlimited food often need nutritional guidance. Wayment, for instance, said she arrived not knowing wheat bread was more nutritious than white.

But rather than targeting an arbitrary number, Taylor emphasizes “fueling the body God gave you.” (She isn’t Mormon, but most of her athletes are; Taylor herself grew up in a conservative Sikh family, which she said helps her relate.) She nourishes athletes with healthy treats like Acai bowls and almonds, and tells them not to compare themselves to others, that a healthy body weight looks different for everyone.

A few weeks before NCAAs, the scale in the BYU weight room broke. Taylor told the strength coach not to fix or replace it. “My women are running great and that number does not matter,” she said. Birk-Jarvis said she was annoyed at first, but as time went on, stopped thinking about her weight entirely.

Given the societal and sports-related pressures female athletes face, Taylor knows not everyone will forget so quickly. “No program is immune from the disordered eating problem that exists within distance running,” Taylor said. But she believes the relationships she’s built and the confidence she’s instilled reduces the risk and enable athletes to get help if issues arise.

She regularly discusses the importance of having regular periods, making the topic less taboo by discussing the timing of her own cycle. If an athlete begins missing them, Taylor refers her to the team dietitian or physician, knowing it might require anything from small dietary changes to more intense intervention.

She also asks recruits if they have a history of eating disorders, anxiety, or depression, so she can understand their background and direct them to the sport psychologist or other appropriate resources swiftly if they’re struggling.

She stresses the sisterhood.

During cross-country camp Taylor’s first season, she and the team came up with a slogan: “BYU Run For Her.” Now, you can spy it on her runners’ shoulders and social media accounts.

The “her” signifies each runner’s younger self, “that little girl who fell in love with the sport,” Taylor said. But the pronoun also refers to running for teammates and celebrating each others’ successes.

Balancing competitiveness and camaraderie often proves tricky on a team with so much talent. Wayment, Orton, and Birk-Jarvis all credit Taylor with helping mitigate jealous impulses, in part by airing them. Telling women these feelings make them poor teammates only adds guilt and shame on top of envy. “You have to validate those feelings and let women know it’s okay—it’s normal to feel that way,” Taylor said.

To defuse envy, Taylor preaches gratitude. The strategy works for Birk-Jarvis. When the emotion arises, “I go through in my head what I’m grateful for about each person on my team, so I keep loving them,” she said.

On Taylor’s advice, Orton began keeping a gratitude journal, a practice she said kept her focused on her own process. For instance, when she was injured last year, she channeled appreciation at how well Birk-Jarvis was running. They’d trained together before her injury, so Orton recognized what Birk-Jarvis’ success meant for her own potential.

These extra steps take time, Taylor said, but she views them as essential parts of the team’s success. “It’s my job to have the vision of what I want my team to look like, of what I want the culture to be,” she said. “I can't just stand up and say these things without following up and making it real for the team. I feel like these things help connect the dots.”

Cindy is a freelance health and fitness writer, author, and podcaster who’s contributed regularly to Runner’s World since 2013. She’s the coauthor of both Breakthrough Women’s Running: Dream Big and Train Smart and Rebound: Train Your Mind to Bounce Back Stronger from Sports Injuries, a book about the psychology of sports injury from Bloomsbury Sport. Cindy specializes in covering injury prevention and recovery, everyday athletes accomplishing extraordinary things, and the active community in her beloved Chicago, where winter forges deep bonds between those brave enough to train through it.